“The cycles of parasites are often diabolically ingenious. It is to the unwilling host that their ends appear mad. Has earth hosted a new disease – that of the world eaters? Then inevitably the spores must fly. Short-lived as they are, they must fly. Somewhere far outward in the dark, instinct may intuitively inform them, lies the garden of the worlds. We must consider the possibility that we do not know the real nature of our kind. Perhaps Homo sapiens, the wise, is himself only a mechanism in a parasitic cycle, an instrument for the transference, ultimately, of a more invulnerable and heartless version of himself…a biological mutation as potentially virulent in its effects as a new bacterial strain. The fact that its nature appears to be cultural merely enables the disease to be spread with fantastic rapidity. There is no comparable episode in history… To climb the fiery ladder that the spore bearers have used one must consume the resources of a world… Basically man’s planetary virulence can be ascribed to just one thing: a rapid ascent, particularly in the last three centuries, of an energy ladder so great that the line on the chart representing it would be almost vertical… Western man’s ethic is not directed toward the preservation of the earth that fathered him. A devouring frenzy is mounting as his numbers mount. It is like the final movement in the spore palaces of the slime molds. Man is now only a creature of anticipation feeding upon events.”

“The World Eaters”from Loren Eiseley, The Invisible Pyramid, 1970

I

It came to me in the night, in the midst of a bad dream, that man, like the blight descending on a fruit, is by nature a parasite, a spore bearer, a world eater. The slime molds are the only creatures on the planet that share the ways of man from his individual pioneer phase to his final immersion in great cities. Under the microscope one can see the mold amoebas streaming to their meeting places, and on one would call them human. Nevertheless, magnified many thousand times and observed from the air, their habits would appear close to our own. This is because, when their microscopic frontier is gone, as it quickly is, the single amoeboid frontiersmen swarm into concentrated aggregations. At the last they thrust up overtoppling spore palaces, like city skyscrapers. The rupture of these vesicles may disseminate the living spores as far away proportionately as man’s journey to the moon.

It is conceivable that in principle man’s motor through-ways resemble the slime trails along which are drawn the gathering mucors that erect the spore palaces, that man’s cities are only the ephemeral moment of his spawning – that he must descend upon the orchard of far worlds or die. Human beings are a strange variant in nature and a very recent one. Perhaps man has evolved as a creature whose centrifugal tendencies are intended to drive it as a blight is lifted and driven, outward across the night.

I do not believe, for reasons I will venture upon later, that this necessity is written in the genes of men, but it would be foolish not to consider the possibility, for man as an interplanetary spore bearer may be only at the first moment of of maturation. After all, mucoroides and its relatives must once have performed their act of dissemination for the first time. In man, even if the feat is cultural, it is still possible that some incalculable and ancient urge lies hidden beneath the seeming rationality of institutionalised science. For example, a young space engineer once passionately exclaimed to me, “ We must give all we have…” It was as though he were hypnotically compelled by obscure chemical, acrasin, that draws the slime molds to their destiny. And is it not true also that observers like myself are occasionally bitterly castigated for daring to examine the motivation of our efforts toward space? In the intellectual climate of today one should strive to remember the words that Herman Melville accorded his proud, fate-confronting Captain Ahab, “All my means are sane, my motive and my object are mad.”

The cycles of parasites are often diabolically ingenious. It is to the unwilling host that their ends appear mad. Has earth hosted a new disease – that of the world eaters? Then inevitably the spores must fly. Short-lived as they are, they must fly. Somewhere far outward in the dark, instinct may intuitively inform them, lies the garden of the worlds. We must consider the possibility that we do not know the real nature of our kind. Perhaps Homo sapiens, the wise, is himself only a mechanism in a parasitic cycle, an instrument for the transference, ultimately, of a more invulnerable and heartless version of himself.

Or, again, the dark may bring him wisdom.

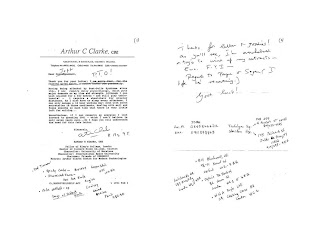

I stand in doubt as my forbears must once have done at the edge of the shrinking forest. I am a man of the rocket century; my knowledge, such as it is, concerns our past, our dubious present, and our possible future. I doubt our motives, but I grant us the benefit of the doubt and, like Arthur C. Clarke, call it, for want of a better term, “childhood’s end.” I also know, as did Plato, that one who spent his life in the shadow of great wars may, like a captive, blink and be momentarily blinded when released into the light.

There are aspects of the world and its inhabitants that are eternal, like the ripples marked in stone on fossil beaches. There is a biological preordination that no one can change. These are seriatim events that only the complete reversal of time could undo. An example would be the moment when the bats dropped into the air and fluttered away from the insectivore line that gave rise to ourselves. What fragment of man, perhaps a useful fragment, departed with them? Something, shall we say, that had it lingered, might have made a small, brave, twilight difference in the mind of man.

There is a part of human destiny that is not fixed irrevocably but is subject to the flying shuttles of chance and will. Everyone imagines that he knows wha it possible and what is impossible, but the whole of time and history attest our ignorance. One evening, in a drab and heartless area of the metropolis, a windborne milkweed seed circled my head. On impulse I seized the delicate aerial orphan which otherwise would have perished. Its long midwinter voyage seemed too favourable an augury to ignore. Placing the seed in my glove, I took it home into the suburbs and found a field in which to plant it. Of a million seeds blown on a vagrant wind into the city, it alone may survive.

Why did I bother? I suppose, in retrospect, for the sake of the future and the memory of the bats whirling like departing thoughts from the tree of ancestral man. Perhaps, after all, there lingered in my reflexes enough of a voyager to help all travellers on the great highway of the winds. Or perhaps I am not yet totally a planet eater and wished that something green might survive. A single impulse, a hand outstretched to an alighting seed, suggests that something is still undetermined in the human psyche, that the time trap has not yet closed inexorably. Some aspect of man that has come with him from the sunlit grasses is still instinctively alive and being fought for. The future, formidable as a thundercloud, is still inchoate and unfixed upon the horizon.

II

Man is a “tinkerer playing with ideas and mechanisms,” comments a recent and very able writer upon technology, R.J. Forbes. He goes on to state that, if those impulses were to disappear, man would cease to be a human being in the sense that we know. It is necessary to concede to Forbes that for Western man, Homo faber, the tool user, the definition is indeed appropriate. Nevertheless, when we turn to the people of the wilderness we must place certain limitations upon the words. That man has utilized tools throughout his history is true, but that man has been particularly inventive or a tinkerer in the sense of seeking constant innovation is open to question.

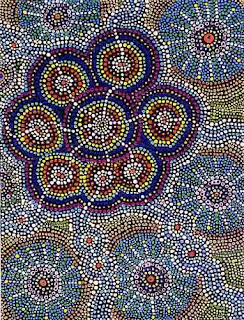

Students of living primitives in backward areas such as Australia have found them addicted to immemorial usage in both ideas and tools. There is frequently a prejudice against the kind of change to which our own society has only recently adjusted. Such behaviour is viewed askance as disruptive. The society is in marked ecological balance with its surroundings, and any drastic innovation from within the group is apt to be rejected as interfering with the will of the divine ancestors.

Not many years ago I fell to chatting with a naturalist who had had a long experience among the Cree of the northern forests. What had struck him about these Indians, even after considerable exposure to white men, was their remarkable and yet, in our terms, “indifferent” adjustment to their woodland environment. By indifference my informant meant that while totally skilled in the use of everything in their surroundings, they had little interest in experiment in a scientific sense, or in carrying objects about with them. Indeed they were frequently very careless with equipment or clothing given or loaned to them. Such things might be discarded afer use of left hanging casually on a branch. One was left with the impression that these woodsmen were, by our standards, casual and feckless. Their reliance upon their own powers was great, but it was based on long traditional accommodation and a psychology by no means attuned to the civilized innovators’ world. Plant fibers had their uses, wood had its uses, but everything from birch bark to porcupine quills were simply “given.” Raw materials were always at hand, to be ignored or picked up as occasion demanded.

One carried little, one survived on little, and little in the way of an acquisitive society existed. One lived amidst all one had use for. If one shifted position in space the same materials were again present to be used. These people were ignorant of what Forbes would regard as the technological necessity to advance. Until the intrusion of whites, their technology had been long frozen upon a barely adequate subsistence level. “Progress” in Western terms was an unknown word.

Similarly I have heard the late Frank Speck discuss the failure of the Montagnais-Naskapi of the Labrador peninsula to take advantage, in their winter forest, either of Eskimo snow goggles, for which they substituted a mere sprig of balsam thrust under the cap, or of the snow house, which is far more comfortable than their cold and draft-exposed wigwams. The same indifference toward technological improvement or the acceptance of innovations from outside thus extended even to their racial brothers, the Eskimo. Man is a tool user, certainly, whether of the stone knife or less visible hunting magic. But that he is an obsessive innovator is far less clear. Tradition rules in the world’s outlands. Man is not on this level driven to be inventive. Instead he is using the sum total of his environment almost as a single tool.

There is a very subtle point at issue here. H.C. Conklin, for example, writes about one Philippine people, the Hanunoo, that their “activities require an intimate familiarity with local plants…Contrary to the assumption that subsistence level groups never use but a small segment of the local flora, ninety-three percent of the total number of native plant types are recognized…as culturally significant.” As Claude Levi-Strauss has been at pains to point out, this state of affairs has been observed in many simple cultures.

Scores of terms exist for objects in the natural environment for which civilized man has no equivalents at all. The latter is engaged primarily with his deepening shell of technology which either exploits the natural world or thrusts it aside. By contrast, man in the earlier cultures was so oriented that the total natural environment occupied his exclusive attention. If parts of it did not really help him practically, they were often inserted into magical patterns that did. Thus man existed primarily in a carefully reorganized nature – one that was watched, brooded over, and managed by magico-religious as well as practical means.

Nature was actually as well read as an alphabet; it was the real “tool” by which man survived with a paucity of practical equipment. Or one could say that the tool had largely been forged in the human imagination. It consisted of the way man had come to organize and relate himself to the sum total of his environment. This world view was comparatively static. Nature was sacred and contained powers which demanded careful propitiation. Modern man, on the other hand, has come to look upon nature as a thing outside himself – an object to be manipulated or discarded at will. It is his technology and its vocabulary that makes his primary world. If, like the primitive, he has a sacred center, it is here. Whatever is potential must be unrolled, brought into being at any cost. No other course is conceived as possible. The economic system demands it.

Two ways of life are thus arrayed in final opposition. One way reads deep, if sometimes mistaken, analogies into nature and maintains toward change a reluctant conservatism. The other is fiercely analytical. Having consciously discovered sequence and novelty, man comes to transfer the operation of the world machine to human hands and to install change itself as progress. A reconciliation of the two views would seem to be necessary if humanity is to survive. The obstacles, however, are great.

Nowhere are they better illustrated than in the decades-old story of an anthropologist who sought to contact a wild and untouched group of aborigines in the red desert of central Australia. Traveling in a truck loaded with water and simple gifts, the scientist finally located his people some five hundred miles from the nearest white settlement. The anthropologist lived with the bush folk for a few weeks and won their confidence. They trusted him. The time came to leave. Straight over the desert ran the tracks of his car, and the aborigines are magnificent trackers.

Things were not the same when their friend had left; something had been transposed or altered in their landscape. The gifts had come so innocently. The little band set out one morning to follow the receding track of their friend. They were many days in drifting on the march, drawn on perhaps by that dim impulse to which the slime molds yield. Eventually they came to the white man’s frontier town. Their friend was gone, but there were other and less kindly white men. There were also drink, prostitution, and disease, about which they were destined to learn. They would never go back to the dunes and the secret places. In five years a begging and degraded remnant would stray through the outskirts of the settlers’ town.

They had learned to their cost that it is possible to wander out of the world of the ancestors, only to become an object of scorn in a world directed to a different set of principles for which the aborigines had no guiding precedent. By leaving the timeless land they had descended into hell. Not all the tiny beings of the slime mold escape to new pastures; some wander, some are sacrificed to make the spore cities, and but a modicum of the original colony mounts the winds of space. It is so in the cities of men.

III

Over a century ago Samuel Taylor Coleridge ruminated in one of his own encounters with the universe that “A Fall of some sort or other – the creation as it were of the non-absolute – is the fundamental postulate of the moral history of man. Without this hypothesis, man is unintelligible; with it every phenomenon is explicable. The mystery itself is too profound for human insight.”

In making this observation Coleridge had come very close upon the flaw that was to create, out of a comparatively simple creature, the world eaters of the twentieth century. How, is a mystery to be explored, because every man on the planet belongs to the same species, and every man communicates. A span of three centuries has been enough to produce a planetary virus, while on that same planet a few lost tribesmen with brains the biological equivalent of our own peer in astonishment form the edges of the last wilderness.

One of the scholars of the scientific twilight, Joseph Glanvill, was quick to intimate that to posterity a voyage to the moon “will not be more strange than one to America.” Even in 1665 the ambitions of the present century had entered human consciousness. The paradox is already present. There is the man Homo sapiens who in various obscure places around the world would rarely think of altering the simple tools of his forefathers, and, again, there is this same Homo sapiens in a wild flurry of modern thought patterns reversing everything by which he had previously lived. Such an episode parallels the rise of a biological mutation as potentially virulent in its effects as a new bacterial strain. The fact that its nature appears to be cultural merely enables the disease to be spread with fantastic rapidity. There is no comparable episode in history.

There are two things which are basic to an understanding of the way in which the primordial people differ from the world eaters, ourselves. Coleridge was quite right that man no more than any other living creature represented the absolute. He was finite and limited, and this his ability to wreak his will upon the world was limited. He might dream of omniscient power, he might practice magic to obtain it, but such power remained beyond his grasp.

As a primitive, man could never do more than linger at the threshold of the energy that flickered in his campfire, nor could he hurl himself beyond Pluto’s realm of frost. He was still within nature. True, he had restructured the green world in his mind so that it lay slightly ensorcelled under the noonday sun. Nevertheless the lightning still roved and struck at will; the cobra could raise its deathly hood in the peasant’s hut at midnight. The dark was thronged with spirits.

Man’s powerful, undisciplined imagination had created a region beyond the visible spectrum which would sometimes aid and sometimes destroy him. Its propitiation and control would occupy and bemuse his mind for long millennia. To climb the fiery ladder that the spore bearers have used one must consume the resources of a world. Since such resources are not to be tapped without the drastic reordering of man’s mental world, his final feat has as its first preliminary the invention of a way to pass knowledge through the doorway of the tomb – namely, the achievement of the written word.

Only so can knowledge be made sufficiently cumulative to challenge the stars. Our brothers of the forest have not lived in the world we have entered. They do not possess the tiny figures by which the dead can be made to speak from those great cemeteries of thought known as libraries. Man’s first giant step for mankind was not through space. Instead it lay through time. Once more in the words of Glanvill, “That men should speak after their tongues were ashes, or communicate with each other in differing Hemisphears, before the Invention of Letters could not but have been thought a fiction.”

In the first of the world’s cities man had begun to live against the enormous backdrop of the theatre. He had become self-conscious, a man enacting his destiny before posterity. As ruler, conqueror, or thinker he lived, as Lewis Mumford has put it, by and for the record. In such a life both evil and good come to cast long shadows into the future. Evil leads to evil, good to good, but frequently the former is the most easy for the cruel to emulate. Moreover, when invention lends itself to centralized control, the individualism of the early frontiers easily gives way to routinized conformity. If life is made easier it is also made more dependent. If artificial demands are stimulated,resources must be consumed at an ever-increasing pace.

As in the microscopic instance of the slime molds, the movement into the urban aggregations is intensified. The most technically advanced peoples will naturally consume the lion’s share of the earth’s resources. Thus the United States at present, representing some six percent of the world’s population, consumes over thirty-four percent of its energy and twenty-nine percent of its steel. Over a billion pounds of trash are spewed over the landscape in a single year. In these few elementary facts, which are capable of endless multiplication, one can see the shape of the future growing – the future of a planet virus Homo sapiens as he assumes in his technological phase what threatens to be his final role.

Experts have been at pains to point out that the accessible crust of the earth is finite, while the demand for minerals steadily increases as more and more societies seek for themselves a higher, Westernized standard of living. Unfortunately many of these sought-after minerals are not renewable , yet a viable industrial economy demands their steady output. A rising world population requiring an improved standard of living clashes with the oncoming realities of a planet of impoverished resources.

“We live in an epoch of localized affluence,” asserts Thomas Lovering, an expert on mineral resources. A few shifts and subterfuges may, with increasing effort and expense, prolong this affluence, but no feat of scientific legerdemain can prevent the eventual exhaustion of the world’s mineral resources at a time not very distant. It is thus apparent that to apply to Western industrial man the term “world eater” is to do so neither in derision nor contempt. We are facing, instead, a simple reality to which, up until recently, the only response has been flight – the flight outward from what appears unsolvable and which threatens, in the end, to leave an impoverished human remnant clinging to an equally impoverished globe.

So quick and so insidious has been the rise of the world virus that its impact is just beginning to be felt and its history to be studied. Basically man’s planetary virulence can be ascribed to just one thing: a rapid ascent, particulary in the last three centuries, of an energy ladder so great that the line on the chart representing it would be almost vertical. The event, in the beginning, involved only Western European civilization. Today it increasingly characterizes most of the planet.

The earliest phase of the human acquisition of energy beyond the needs of survival revolves, as observed earlier, around the rise of the first agricultural civilizations shortly after the close of the Ice Age. Only with the appearance of wealth in the shape of storable grains can the differentiation of labor and of social classes, as well as an increase in population, lay the basis for the expansion of the urban world. With this event the expansion of trade and trade routes was sure to follow. The domestication of plants and animals, however, was still an event of the green world and the sheepfold. Nevertheless it opened a doorway in nature that had lain concealed from man.

Like all earth’s other creatures, he had previously existed in a precarious balance with nature. In spite of his adaptability, man, the hunter, had spread across the continents like thin fire burning over a meadow. It was impossible for his number to grow in any one place, because man, multiplying, quickly consumes the wild things upon which he feeds and then himself faces starvation. Only with plant domestication is the storage granary made possible and through it three primary changes in the life of man: a spectacular increase in human numbers; diversification of labor; the ability to feed from the countryside the cities into which man would presently stream.

After some four million years of lingering in nature’s shadow, man would appear to have initiated a drastic change in the world of the animal gods and the magic that had seen him through millennial seasons. Such a change did not happen overnight, and we may never learn the details of its incipient beginnings. As we have already noted, at the close of the Ice Age, and particularly throughout the northern hemisphere, the big game, the hairy mammoth and mastodon, the giant long-horned bison, had streamed away with the melting glaciers. Sand was blowing over the fertile plains of North Africa and the Middle East. Gloomy forests were springing up in the Europe of the tundra hunters. The reindeer and musk ox had withdrawn far into the north on the heels of the retreating ice.

Man must have turned, in something approaching agony and humiliation, to the women with their digging sticks and arcane knowledge of seeds. Slowly, with greater ceremonial, the spring and harvest festivals began to replace the memory of the “gods with the wet nose,” the bison gods of the earlier free-roving years. Whether for good or ill the world would never be the same. The stars would no longer be the stars of the wandering hunters. Halley’s comet returning would no longer gleam on the tossing antlers and snowy backs of the moving game herds. Instead it would glimmer from the desolate tarns left by the ice in dark forests or startle shepherds watching flocks on the stony hills of Judea. Perhaps it was the fleeting star seen by the three wise men of legend, for a time of human transcendence was approaching.

To comprehend the rise of the world eaters one must leap centuries and millennia. To account fo the rise of high-energy civilization is as difficult to explain the circumstances that have gone into the creation of man himself. Certainly the old sun-plant civilizations provided leisure for meditation, mathematics, and transport energy through the use of sails. Writing, which arose among them, created a kind of stored thought-energy, an enhanced social brain.

All this the seed-and-sun world contributed, but no more. Not all of these civilizations left the traditional religious round of the seasons or the worship of the sun-kings installed on Earth. Only far on in time, in west Europe, did a new culture and a new world emerge. Perhaps it would be best to limit our exposition to one spokesman who immediately anticipated its appearance. “If we must select some one philosopher as the hero of the revolution in scientific method,” maintained William Whewell, the nineteenth-century historian, “beyond all doubt Francis Bacon occupies the place of honor.” This view is based upon four simple precepts, the first of which, form The Advancement of Learning, I will give in Bacon’s own words. “As the foundation,” he wrote, “we are not to imagine or suppose but to discover what nature does or may be made to do.” Today this sounds like a truism. In Bacon’s time it was a novel, analytical,and unheard-of way to explore nature. Bacon was thus the herald of what has been called “the invention of inventions” – the scientific method itself.

He believed also that the thinker could join with the skilled worker – what we today would call the technologist – to conduct experiment more ably than by simple and untested meditation in the cloister. Bacon, in other words, was groping toward the idea of the laboratory, of a whole new way of schooling. Within such schools, aided by government support, he hoped for the solution of problems not to be dealt with “in the hourglass of one man’s life.” In expressing this hope he had recognized that great achievement in science must not wait on the unaided and rare genius, but that research should be institutionalised and supported over the human generations.

Fourth and last of Bacon’s insights was his vision of the future to be created by science. Here there clearly emerges the orientation towards the future which has since preoccupied the world of science and the West. Bacon was pre-eminently the spokesman of anticipatory man. The long reign of the custom-bound scholastics was at an end. Anticipatory analytical man, enraptured by novelty, was about to walk an increasingly dangerous pathway.

He would triumph over disease and his numbers would mount; steam and, later, air transport would link the ends of the earth. Agriculture would fall under scientific management, and fewer men on the land would easily support the febrile millions in the gathering cities. As Glanvill had foreseen, thought would fly upon the air. Man’s telescopic eye would rove through the galaxy and beyond. No longer would men be burned or tortured for dreaming of life on far-off worlds.

There came, too, in the twentieth century to mock the dream of progress the most ruthless and cruel wars of history. They were the first wars fought with total scientific detachment. Cities were fire-bombed, submarines turned the night waters into a flaming horror, the air was black with opposing air fleets.

The laboratories of Bacon’s vision produced the atom bomb and toyed prospectively with deadly nerve gas. “Overkill” became a professional word. Iron, steel, Plexiglas, and the deadly mathematics of missile and anti-missile occupied the finest constructive minds. Even before space was entered, man began to assume the fixed mask of the robot. His courage was unbreakable, but in society there was mounting evidence of strain. Billions of dollars were being devoured in the space effort, while at the same time an affluent civilization was consuming its resources at an ever-increasing rate. Air and water and the land itself were being polluted by the activities of a creature grown used to the careless ravage of a continent.

Francis Bacon had spoken one further word on the subject of science, but by the time that science came its prophet had been forgotten. He had spoken of learning as intended to bring an enlightened life. Western man’s ethic is not directed toward the preservation of the earth that fathered him. A devouring frenzy is mounting as his numbers mount. It is like the final movement in the spore palaces of the slime molds. Man is now only a creature of anticipation feeding upon events.

“When evil comes it is because two gods have disagreed,” runs the proverb of an elder people. Perhapsit is another way of saying that the past and the future are at war in the heart of man. On March 7, 1970, as I sit at my desk the eastern seaboard is swept by the shadow of the greatest eclipse since 1900. Beyond my window I can see a strangely darkened sky, as though the light of the sun were going out forever. For an instant, lost in the dim gray light, I experience an equally gray clarity of vision.

IV

There is a tradition among the little Bushmen of the Kalihari desert that eclipses of the moon are caused by Kingsfoot, the lion who covers the moon’s face with his paw to make the night dark for hunting. Since our most modern science informs us we have come from animals, and since almost all primitives have tended to draw their creator gods from the animal world with which they were familiar, modern man and his bush contemporaries have arrived at the same conclusion by very different routes. Both know their relationship with animals by different ways of logic and different measures of time.

Modern man, the world eater, respects no space and no thing green or furred as sacred. The march of the machines has entered his blood. They are his seed boxes, his potential wings and guidance systems on the far roads of the universe. The fruition time of the planet virus is at hand. It is high autumn, the autumn before winter topples the spore cities. “The living memory of the city disappears,” writes Mumford of this phase of urban life; “its inhabitants live in a self-annihilating moment to moment continuum.” The ancestral center exists no longer. Anonymous millions roam the streets.

On the African veldt the lion, the last of the great carnivores, is addressed by the Bushmen over a kill whose ownership is contested. They speak softly the age-old ritual words for the occasion, “Great Lions, Old Lions, we know that you are brave.” Nevertheless the little, almost weaponless people steadily advance. The beginning and the end are dying in unison and the one is braver than the other. Dreaming on by the eclipse-darkened window, I know with a sudden pure premonition that Kingsfoot has put his paw once more against the moon. The animal gods will come out for one last hunt.

Beginning on some winter night the snow will fall steadily for a thousand years and hush in its falling the spore cities whose seed has flown. The delicate traceries of the frost will slowly dim the glass in the observatories and all will be as it had been before the virus had awakened. The long trail of Halley’s comet, once more returning, will pass like a ghostly matchflame over the unwatched grave of the cities. This has always been their end, whether in the snow or in the sand.